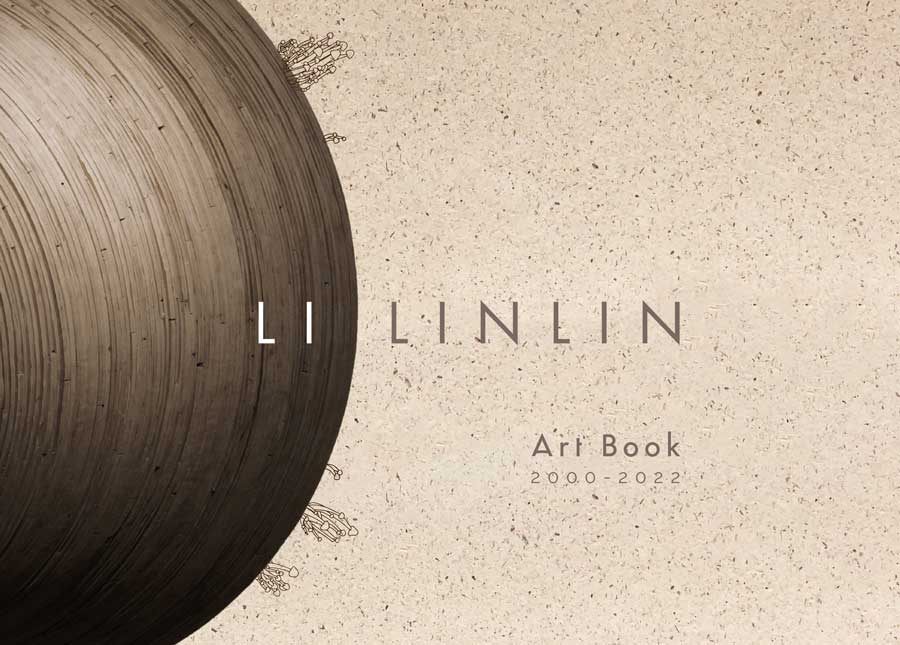

Solo Exhibition of Li Linlin: The Protector

05/09/2022-15/11/2022

At the AimerArt Museum, Beijing

Curator: Mei Huang

Curatorial Concept:

Li Linlin: As a Woman, Living in this moment - by Mei Huang

Li Linlin and I first met in 2015. I can’t remember the specific activities or exhibitions that we participated together, what’s still in my mind was the shock when I saw her works for the first time: there was such a violent, persistence and destructive power in the body of this beautiful shy girl. What a great contrast!

Indeed, Linlin’s early works have a sort of brutally wounded and dark fairy tale-like aesthetic. I believe it is related with the growth experience of our generation in Chin after 1985. As an only child, in those adolescence nights when the internet and smartphones have not yet become popular, the only things that can comfort the lonely and curious teenagers are dark and painful love literary novels, secret explorations and forbidden fruit between boys and girls, the hysterical songs from Marilyn Manson; plus those intriguing and long-waited western contemporary art catalogues from import local bookstores. The End of the Game (2017) and Who Will Comfort me (2017) are two of the more representative works in Li Linlin’s early creation stage where she took her inspirations from Chapman brothers and Kiki Smith. Her installations are huge with stunning details: inside the massive wooden house, there are large number of dolls presented in grotesque poses, surrounding viewers oppressively. These manikins copulate in twisted ways, some of their limbs are scattered. Friendly teddy bears, moldy bones, big iron cages and injured bare feet, these figurative allegorical symbols and cruel adult fairy tales form the backbone of Linlin’s early works.

She is very good at using and handling the hidden metaphors, this makes the Mushroom series particularly outstanding. Layers of densely packed mini fungus grow on different utensils one by one. Although Linlin’s interpretation for this series is “plants containing dark energy are growing strong in the shadows”, it is unavoidable that the image of small mushroom and male genitalia are highly overlapped and associated. In the shadows and dampness, these little mushrooms — born on death, skeletons and antiques, are like miniature candies full of desire, blossoming with lust and temptation in the decay of time. And full of vigorous desire is a characteristic of youth, it is a powerful psychedelic drug against aging and death. Knowing what is poisonous, but cannot be stoped from sinking. This metaphorical contrast is both addictive and hopeless.

In Linlin’s early works, unspeakable erotic desires are always included, there are some kind of fantasy or certain imaginations that could only be lewd in the mind. Such boldness and honesty are rare among Chinese female artists. In China, and even in Asia, women’s lust and desire are rarely mentioned topics. We ourselves hardly ever think about and admit that we also expect and enjoy physical orgasms, as well as what our partner or ourselves can bring to us, and where our desires lead us to. Desires are not shameful, and facing up to one’s needs is neither because of bad conduct nor to be “the Ethical Slut”. Perhaps too many Asian women’s lust is suppressed by social persuasion, the virtues of a good wife and a good mother, and the heavy burden of parenting and life; which has evolved into an unacceptable metaphor, or is directly castrated and abandoned.

In 2019, I visited Li Linlin’s studio in Rome Lake. The transportation from downtown Beijing to the studio was extremely inconvenient, and it took me about two hours to get there by taxi. This small, two-floors studio was converted from a factory which was filled with materials of her large-scale installations: giant elephants that covered in bags, life-size plastic mannequins stacked on top of each other, many mushroom sculptures, and full of documents and dairy papers that scattered both on the table and floor. It’s in winter, there’s no heating in her studio, and the winter temperature in Beijing was always below zero. I distinctly remember my frozen fingers and hard-to-move steps. It’s hard to imagine how she could continue to work in such an environment when she was alone. She showed me many manuscripts and daily notes, “I like to jot down my own thoughts and emotions on a piece of paper at anytime, anywhere; so I don’t forget about them, and I often make them part of my work.” Linlin explained me with smile and enthusiasm.

Sigmund Freud, in his essay A Note Upon The Mystic Writing-Pad (1925), referred to the relationship of note-taking and emotions/thoughts — there was a direct psychological connection between system Pcpy.-Cs and the perception of subconscious mind. Day after day, every little thing that stimulates our psyche seems normal, and the triggered emotions will soon disappear and be forgotten by the brain; however these events leave a certain track in our subconscious. To some extent, it even determines what kind of person we would become in the future. For instance, by documenting every moment, all the conversations and used items surround him, artist Christian Boltanski used to fight the emptiness of death and find the meaning of life in his works at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London. This reminds me of Lin Linlin’s work Reconstruction Series: Songs From My Heart (2019) which is commissioned by the exhibition Silent Narrative in 2019: Entering the tiny little room below this huge installation, the viewer can feel and touch all the artist’s daily necessities, which including hammock, pillow, small table lamp, and as well as densely packed note stickers and diaries on the walls. Everyone can seek the shadow of childhood in their subconsciousness from Linlin’s installations, especially feeling the unyielding and savage energy from the artist that grows wildly, just like weeds or thorns and vines enlarge at the root of the dilapidated wall.

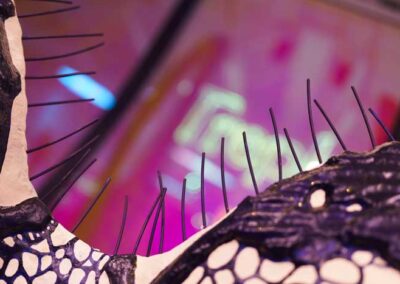

A major turning point in Li Linlin’s work came in 2018-2019, the year she became a mother. Since 2019, Linlin’s works have abandoned the previous relatively complicated forms and developed towards the direction of minimalism and abstraction, the volume of the installations is also larger than before. Crazy Evolution (2021) is an eye-opening work. The depth that longer than 30 meters and the super high ceiling of more than 20 meters from the Yinchuan MOCA have given Li Linlin a lot of creative space. However, it’s very challenging at the same time — the pros and cons of the work are magnified by the venue. Multiple giant pyramids broke out from all sides of walls and pierced into the originally peaceful field. The pyramid was constructed by splicing wood with triangles as cuttings points, with blue lighting panels in the middle. The light at the top was refracted in the exhibition hall through the panels and prisms, forming waves of cool lights and shadows. They were illustrated in the space painted with warm yellow walls, thus a chilling contrast was built up. Between the giant pillars, there were four small red chairs, cute and fragile, like a resting place in a dangerous field. The viewers can sit on them and feel the physical oppression of the space by the giant cones, as well as enjoy the fluctuation of light and shadow. This play with architectural space and light projection reminds me of the spiky domes and daylight-filled stained glass windows from Gothic Catholic churches. The difference is that the dome of the church is pointed upward, which means infinite extension. It brings the believers and prayers to reach the place where they could connect with the heaven. On the contrary, the giant pyramid of Crazy Evolution pierced through the private, safe and warm space just like the cruel reality did. Only the small red seat was our remaining childishness and innocence.

New Born (2019) is another good example: the wooden giant egg is smooth and moist, as a mother’s pregnant belly with stretch marks, or a uterus — the wrinkled mechanism is a breeding ground for egg-landing and its development. It also looks like a soft breast that changed to hard with stretch marks during lactation. Although it’s painful, she bravely takes on the burden of bedding the young. It is very much related to the primordial maternal attraction from the Venus of Willendorf (C.25,000 BP). The wood excuses a natural spice, it’s neither made by a solid texture, nor hard and cold as steel. It has the gentleness and tolerance of the mother earth, and also the desolation of returning to reincarnation after suffer. It’s not difficult to find out that tenderness and maternal love has gradually been integrated into Li Linlin’s later works, we can often see pairs of large and small installations appearing: mother-child like elephants sewn on cloth, a pair of big-small skeletons buried in the soil, and two wool socks on the branches. The dark fairly tales of the early work stages and the lust of adolescence have slowly transformed into a warm maternal love to the cub. However, it is worth pondering that many Chinese female artists with successful careers don’t want themselves and their works to have too much connection with “female” and especially “feminism”, because “men don’t show their works with ‘male label’ when they have exhibitions”. Instead, Linlin doesn’t reject the definitions of “woman” and “mother”. As a female artist, having a self-identity to be a woman is indeed something we cannot avoid: when we were born, from our bodies, educations, and the way we are treated by the society make us a woman; our feedback to the world and the works we created are also by some extend affected by this fact. Rather than denying and escaping, it’s better to generously admit and enjoy the differences and diversity by accepting and facing all limitations and advantages.

In the circle of friends and the art field, Linlin is recognized as a super hard worker. She overcame and endured many difficulties and hardships, and has been tirelessly pursuing her imaginations and ideas. During years of friendship, the cooperation in 2019, more than a year of preparation for this book and an upcoming exhibition, we have shared a lot of life experiences. If it’s me, I don’t think I could hold on as strong as she did. Linlin once told me: no matter the future or the outcome, she only knows that she will make art all her life, because it’s what she loves. I’m very moved and truly respect by what she said. This book, which collects Li Linlin’s works from 2012 to 2022, is a brief summary of her main artistic creations in these years. In addition to Linlin’s pieces, the book also features two articles from professors/art critics/curators Laia Manonelles and Herman Bashiron. Special thanks to artist Xiang Jing and curator/professor He Guiyan for their high affirmation reviews to Linlin’s work. After talk to Linlin, we’d also like to take this opportunity to commemorate and cherish our common mentor artist Cut Xiuwen. Although she has passed away many years, her perseverance and unyielding quality as an outstanding Chinese contemporary female artist has always inspired younger generations.

This book marks the beginning of a new phase in Linlin’s artistic journey, with a bright future ahead.